“In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.”

It’s incredible how much ten short words can do, isn’t it? These were the first ten words I ever read by J.R.R. Tolkien, and they changed my life in several ways: by introducing me to my favorite author, by rekindling a dormant love for linguistics, and by starting me on a road that would eventually lead me (many years down the road) to a makeshift recording booth in my closet, where I have the pleasure of co-hosting a podcast that has brought me in touch with similarly minded Tolkien lovers all over the world.

I suspect many of you reading this had your first entry into Tolkien’s world through these ten words as well. Maybe in the last sixteen years, as Peter Jackson’s movie adaptations have introduced more and more people to Middle-earth, it’s become more common for new readers to start with The Lord of the Rings before The Hobbit, on the strength of the movies (I’m just guessing there). But I suspect that most readers out there have, for one reason or another, decided to start with The Hobbit, and are first introduced to Tolkien’s writing through these ten words. I have no proof of this, but if anyone reading this has even taken or seen a poll, I welcome your comments below.

The first sentence of The Hobbit

is a portal of words through the wall

between our primary world

and Tolkien’s secondary world.

So, sure. I read The Hobbit first, and so did many of us. But one thing that I imagine sets my experience apart a bit is that I was captivated by these ten words before I ever opened a book by Tolkien (and believe it or not, Rankin/Bass Productions had nothing to do with it either).

Although as a teenager I had played my fair share of Dungeons & Dragons, and fantasy novels were already starting to collect on the one bookshelf I could fit in my bedroom, I didn’t learn about Tolkien from any of these typically Tolkien-tangential interests. I learned about Tolkien by reading the ten words above quoted in a book about something completely unrelated — a rock band:

A generation earlier [than 1966], a similarly bored professor, J.R.R. Tolkien, had found relief by scribbling on an empty page of one of his students’ papers, ‘In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit’—thereby sparking the mythical saga of Middle-earth that was to become a virtual bible for Britain’s emerging underground.1

This account of The Hobbit’s creation grabbed me instantly, and the story is one of my favorite details about Tolkien’s life. When I discovered Tolkien at the tender age of fifteen, I had dabbled in writing fantasy and also considered a career in teaching, so you can probably imagine how impressed I was to learn that a college professor started writing a fantasy novel on a blank page of a student’s paper. You can do that?? Count me in! I instantly saw Tolkien as a kind of academic rebel, flouting the rules of pedagogical convention in a desperate need to follow his heart’s desire and write about something called a hobbit, whatever that was. And while I’ve since learned enough about Tolkien’s life to realize that my vision of him was very romanticized, I’ve also learned enough to realize that he remained an academic (and literary) rebel throughout his life. I deeply admired that kind of rebellion as a young man: the kind of rebellion that creates, rather than destroys. I still do.

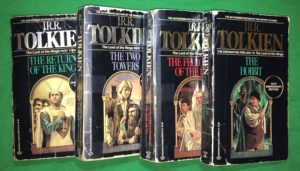

So what did I do? You know the answer to that. I went right out and spent some hard-earned allowance money on a box set of mass-market paperbacks of The Hobbit and The Lord of the Rings. I still have those books, though I have since lost the box, and I almost lost the covers:

Breathe in the ‘80s fantasy art. And the early ’00s Scotch-tape rebinding job.

When I started reading The Hobbit for the first time, of course I came in with some assumptions. One of those assumptions was that I was reading a “virtual bible” for British counterculture of the 1960s (a bit of an exaggeration, I think now). I think it was because of that assumption that I didn’t initially make the common assumption that The Hobbit was that other thing people call it: a “children’s book.” I remember assuming I was starting in on a serious work of fantasy, and I approached it as such. It was only later — probably once I had moved on to The Lord of the Rings and realized just how deep this world would go, and certainly after I started talking to friends at school about Tolkien — that I started to think of The Hobbit as less serious than the other Middle-earth works. That’s a perception that would eventually take hold of me, and unfortunately would stay with me for many years.

But on the first reading? Not at all. I read those ten words and I felt the wonder right away. Looking at them again now, it’s easy to see why. The first sentence of The Hobbit is a well-constructed portal of words, a tunnel right through the wall between our primary world and Tolkien’s secondary world. We can actually break the sentence into several parts, every two or three words representing a different point along the path of entry:

- “In a hole” – We don’t know yet that the word hole has a meaning in hobbit-vernacular roughly equivalent to our word house. Tolkien plays on this by not defining it, and by allowing us to interpret it in the more common sense. All we know now — and we know it from the very beginning — is that there is a hole. This immediately piques our curiosity. What’s it a hole in? What’s inside the hole? We are shown the hole and invited, perhaps dared, to look inside.

- “in the ground” – Okay, well that answers one of our questions about the hole. But now we’re not so sure we want to go in, are we? The language that it’s “not a nasty, dirty, wet hole” is coming very soon, but we don’t know it yet. In fact, knowing that it’s in the ground (and not in, say, a freshly laundered bed sheet) should lead us to the conclusion that it is precisely the kind of hole that should be “nasty, dirty, wet” and “filled with the ends of worms”. Maybe we’re scared. Maybe we should be.

- “there lived” – Whew. Okay, something lives in the hole. Of course, we don’t know what yet, but at least something lives there. I mean, it’s not like something died there. If something calls it home, it can’t be all bad, right? Maybe we’re not as scared. Or maybe we’re uncertain, but hopeful. And we’re at least curious enough to keep reading and find out if the rest of the sentence tells us what lived there.

- “a hobbit” – Oh. Well, we’re not quite sure what that is, but it doesn’t sound too threatening. And it’s familiar, at least in a certain sense. We should have at least expected to find one somewhere in the book, because it’s the title. So now we’re really curious, and ready to settle in to learn exactly what a hobbit is, starting on the next page but not really finding out until right around 280 pages later.

Of course, this all happens in ten words, much too quickly for us to parse it out so completely. But it’s all there, as tangible and sequential as stepping through the back of a wardrobe or falling down a rabbit hole: we enter (appropriately) at the first word “in”, and by the last word — pretty quickly, just as Lucy Pevensie meets Tumnus or Alice meets her white rabbit — we have already met our first resident of that world.

Of course, I’m mixing up my metaphor here, because when we first enter the book, the world we find (and the resident) is not all that different from our own. Bilbo’s hobbit-hole is comfortable and welcoming, and we can easily imagine ourselves living in it and in the small world he inhabits, as displayed on the map of the Country Round that hangs in Bilbo’s hall marked with red ink. Bilbo must go through his own transition (or rather, have it forced upon him) to enter into a wider world, a Wilderland of dwarves, goblins, and dragons. This is key to the story: Bilbo’s relatability is part of what makes him such a compelling character, and what’s more, it allows us to discover the hidden fantasy of his world along with him. But we are in that world from the moment we read those ten words, even though we cannot see through the veil to its mysteries yet.

And of course, as anyone who’s read past The Hobbit into The Lord of the Rings, The Silmarillion or beyond, the mysteries just keep coming. The closer we look, the world of Middle-earth just seems, to borrow Alice’s phrase, “Curiouser and curiouser!” (And with that, I promise I am almost done with the Lewis Carroll references, at least until Episode 053 airs next Sunday, September 24.)

I fell down the hobbit hole one summer day in 1991 (I said I was almost done), and over a quarter of a century later, I’m still falling. I’ve noticed that almost every time I go back into Middle-earth, I find something new. I’ve also noticed that re-reading The Hobbit to my children in recent years has (mostly, and perhaps ironically) helped me get past my acquired perception of The Hobbit as a children’s book. I’ve started to find new wonders in The Hobbit as wondrous as those to be found in the deep myths of The Silmarillion and the high fantasy of The Lord of the Rings, and I can’t tell you how much I’m looking forward to giving The Hobbit the full Prancing Pony Podcast treatment.

As we embark on this journey, I want to thank you. Thank you for listening to the podcast and for reading our Prancing Pony Ponderings. Thank you for your comments, for the feedback that helps Alan and I make our podcast a better show and make ourselves constantly strive to be the best hosts we can be. Thank you for the questions that keep us researching and learning more about this world we all love so much, and please keep them coming. The Hobbit may seem like the simplest story in the legendarium, the one we know best; as though familiarity has made it seem smaller and less full of wonders to discover. But I think that together, we will discover something new: something that’s only waiting for a chance to come out.

1 Schaffner, Nicholas. Saucerful of Secrets: The Pink Floyd Odyssey (first edition hardcover, pp. 11-12). This is the first of three mentions of Tolkien in the book, which I find odd considering that — unlike bands like Led Zeppelin, Rush, or members of Yes — Pink Floyd never actually recorded an overtly Tolkien-influenced song. There is one song on their first album about a Gnome, but there’s no mention of him having survived the Goblin-wars of Gondolin.

Excellent Shawn! I enjoyed the personal touch to the analysis of those indeed, special and intriguing 10 words! I can’t wait to see what you have in store for the PPP season 2 on The Hobbit!

Thanks, Amc! I really can’t wait for season 2. I think it’s going to be a lot of fun.

Great! Looking forward to going through The Hobbit with you guys. I just started my Tolkien journey early this year (at the tender age of 36). I read The Hobbit twice then LotR then the Sil. For the past few months I have been emersed in the HoME books as well as Tolkien’s other works and pretty much anything Tolkien I could get my hands on (and the PPPodcast!). I’ve read Biographies and lectures and even delved into the study of Norse and AngloSaxon literature. I’ve come a long way in 9 months but I’m ready to get back to basics for a while. Keep it up guys! I know that I speak for lots of folks when I say that we appreciate what you guys are doing. Thanks!

Thank you, Josh… and wow! That’s an admirable amount of depth you’ve explored in a few short months. I agree, it will be interesting to go back to basics with the knowledge we’ve gained going through The Silmarillion (and some of the other specialized works we’ve explored in specials). I’m glad to have you on the journey with us.

I would say not that The Hobbit is not a children’s book, but rather that children’s literature can be quite serious and wornderful in itself. This holds not only for The Hobbit but for all good children’s books.

Having said that, nicely done. Let us (well, you) reveal the wonders of The Hobbit! And digress!

Thank you, Yariv, and very well said. I’m reminded of one of Tolkien’s comments in “On Fairy-Stories”, in which he says that a love of fairy-tales “does not decrease but increases with age, if it is innate.” Thank you for your thoughts on it.

There is a wonderful cadence you detected early to those famous words, “In a hole in the ground there lived a hobbit.” They just now reminded me of this renowned beginning sentence: “These are the times that try men’s souls.” Also you were wise to realize, like C.S. Lewis did in his book review of The Hobbit, that it is MUCH more than a children’s book.

Indeed it is much more than “just” a children’s book! What’s amazing to me is how I had to become a parent before I was able to figure that out again.

Great personal account, Shawn. What’s fascinating about Tolkien and his readers is stuff like this: I didn’t start with the book but with the Rankin/Bass film, but we’ve ended up in the same place anyway. Such is the inexorable power of Tolkien that it draws you down (down to Goblin-town) to its core and its roots no matter which cave in the Misty Mountains you enter from.

Well said, Jeff. It has a way of drawing us in, and I still feel like I’m being drawn down into the deep places of the world, most recently with the linguistic material. I feel like I can keep going and never stop. I’d love to hear (or read) your personal discovery story sometime.